Applications of

Quantum Physics

Implications of

Quantum Physics

32. Light, Photons and Polarization.

Summary

The polarization states of photons are explained. Polarization experiments on light are described.

A photon is the name given to a ‘piece’ of light. In this treatment, where it is justifiably assumed there are no particles (see

No Evidence for Particles), it refers to a wave function with mass 0, spin 1, and charge 0. Each photon (wave function) travels at the speed of light. If it has wavelength

, its energy is

hc/

and its momentum is

h/

where

c is the speed of light and

h is Planck’s constant.

Each photon has two possible states of

polarization, which is analogous to spin or angular momentum (See

Spin and the Stern-Gerlach Experiment). This can be visualized in the following way: A photon can be thought of (at least classically) as consisting of oscillating electric and magnetic fields. If a photon is traveling in the z direction, its electric field can either oscillate in the x direction, so the photon is represented by

x

x

, or its electric field can be oscillating in the y direction, so it is represented by

y

y

. These are the two states of polarization.

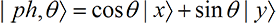

It can also be polarized so its electric field oscillates in any direction, say at an angle

to the x axis. In that case, the photon state can be represented as a (linear)

combination of the

x

x

and

y

y

polarizations,

(32-1)

There are certain materials (such as Polaroid) that act as filters in that they let through only that part of the photon polarized in a certain direction. Schematically, in terms of the wave function, if we have a polarizer

P,x

P,x

that lets through only

x

x

photons, then the

y

y

part is blocked, so

(32-2)

What this translates into experimentally is the following: Suppose we have a beam of light that contains N photons in state (32-1) crossing a given plane per sec., each moving at the speed of light. Then a 100% efficient detector put in the beam will record N ‘hits’ per second. But if we put an

x polarizer in the beam, as is done schematically in (32-2), the detector will record only

N cos2

hits per second. And if we put in a

y polarizer, the detector will record only

N sin2

hits per second. (This is in agreement with the

|ai|2 probability law of principle [

P10] in

The Probability Law.

Thus the polarization state of Eq. (32-1) acts

as if it were composed of both a photon polarized in the

x direction

and a photon polarized in the

y direction. But if we measure, we find an

x

x

photon on a fraction

cos2

of the measurements and a

y

y

photon on a fraction

sin2

of the measurements, but we never find both an

x

x

photon and a

y

y

photon on a single run! Not so easy to understand!

There are crystals that can separate the photon into its

x and

y polarization parts, so that the

x polarized part travels on one path and the

y polarized part travels on another path. One can put a detector in each path, and one can have an observer that looks at each detector. If we send a single photon, in state (32-1), through this apparatus, the wave function of the two detectors plus the observer is still a sum of just two terms:

(32-3)

But now the whole ‘universe,’ photon, detectors and observer, has split into two states. In particular, if you are the observer, there are two states of you! On a fraction

cos2

of the runs, the “

x, yes;

y, no” version will correspond to your perceptions; and on a fraction

sin2

of the runs the “

x, no;

y, yes” version will correspond to your perceptions. On a given run, quantum physics does not say which version will correspond to your perceptions. So this experiment and the state of Eq. (32-3) give another example of quantum physics presenting us with more than one version of reality—one version of you perceiving polarization

x and, at the same time, another version of you perceiving polarization

y.